“Know yourself and know your enemy, and you will be victorious in a thousand battles”

Sun Tzu (The art of war)

Any adventure requires a map and a backpack.

Any project demands a view of the environment around us and an understanding of how we are equiped for the journey.

We must look around and look inside. There will be opportunities around us, but also threats. We have strengths in the backpack, but also weaknesses.

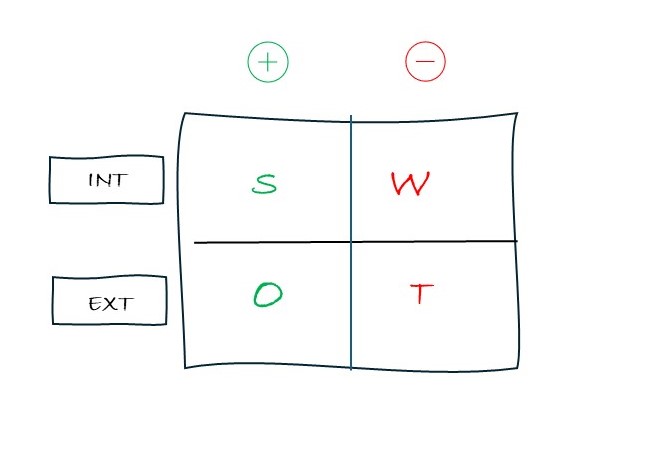

A SWOT analysis is a simple and structured way to check all those internal and external, positive and negative elements and keep them in mind during decision making.

Although it is a business strategy tool, we often propose a personal SWOT in coaching and mentoring projects to facilitate insight at the start of any personal growth project – be it a new career, starting to write your book or starting your trip around the word.

SWOT is often attributed to Albert S.Humpfrey, but the concept started probably earlier. In 1957 Phiip Selznick and others inspired the design strategy school, which followed the principle of aligning internal factors to match the external ones.

The best way to understand how to use it for your project is observing how management teams use it in business strategy planning… when this is done properly. Which unfortunately is not always the case.

How to waste time with a SWOT analysis

First meeting for the sales team with the new manager, just arrived. Expectations in the atmosphere, some excitement because new doors might open, perhaps some fear about new leadership styles. Coffee and a round of personal introductions help to break the ice. We need to start somewhere and the leader wants to understand where we come from and what are our concerns, so he proposes: “Let’s do a SWOT análisis!”

Manager draws a square in the whiteboard and splits it in four sectors. The upper ones are internal factors, the lower are external. The left side is for positive aspects, the right side for negative. Each of the four resulting boxes has a letter: S (for strenghts), W (weaknesses), O (opportunities), T (Threats). She asks the team to populate it.

In a few seconds someone has posted under Strengths: “team’s experience and motivation”, with everyone’s approval.

In Weaknesses, “lack of good marketing support”.

If you don’t like this example, we can imagine the Marketing department doing the exercise and then the weaknesses would probably be “lack of good support from Sales. It could also be lack of good customer service, competitive prices or effective supply chain… anything, as long as the accountable people are not in the room.

A long debate will follow about whether the technology transformation of the market is a threat or an opportunity. “It might be an opportunity if we had decent marketing support but for us it’s a threat”, says someone. To unblock the discussion, the group agrees to write it in both boxes.

After long discussions on each topic and where they belong, this group finally have a table filled with obvious statements, which is of no help at all for the next steps. It gets parked for a later moment. Back to work.

Has this ever happened to you?

Doing a good SWOT analysis

Three common mistakes make the previous example useless.

First, the scope was not clearly defined. What are we analysing? Is it the company, a department, a project team…? The person or team doing it needs a complete and clear vision of the unit to analyze. Otherwise, it is too easy to make things look easy by putting our weaknesses on the shoulders of those who are not in the room.

There is also the lack of experience or ability to observe the environment. It’s usually a good idea to do this in two steps. First, we list the changes observed or expected in the market. Then, we classify them based on their potential effect on our business. Changes which play in our favor are opportunities, while changes that benefit our competitors more than us are threats.

Finally a common mistake is to abandon the process after completing the diagnosis. We don’t do an analysis just to archive it.

Now that we have the SWOT, what are we gonna do with it?

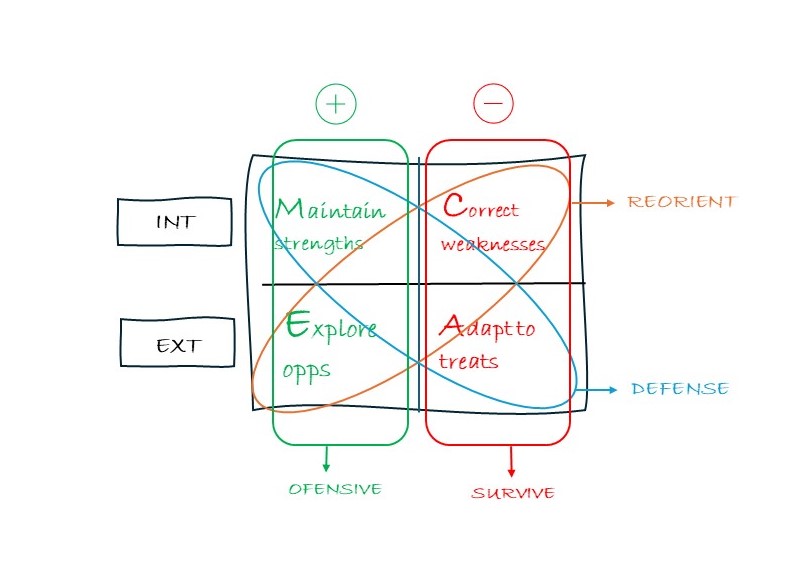

To take decisions using the matrix we need to understand the connections between the different elements. This is done crossing each external element with all the internal elements, and asking:

- For each opportunity, which strengths can help us capitalize on this opportunity? Which of the weaknesses could derail it?

- For each threat, which strengths can prepare us to confront it successfully? Which weaknesses make us vulnerable to it?

Based on this cross analysis we can determine:

• What opportunities do we want to explore?

• Are there threats we must adapt to?

• Which are the key strengths to maintain?

• What weaknesses need to be corrected?

This part of the analysis is often called CAME in Spanish business literatura, an acronym for Correct, Adapt, Maintain and Exploit

Any strategy is a decision. The matrix shows us facts, but it is up to us to choose which opportunities are most attractive, which threats are critical, and where to put our efforts. If we avoid the “I want it all” mistake, we will decide on a strategy that can fall into one of four types.

1. The offensive strategy: maintain strengths to exploit opportunities

In 2020, when the world urgently asked for vaccines against the new coronavirus, ModeRNA had been accumulating knowledge about the functions of messenger RNA for ten years based on the discoveries of Karikó and Weissmann that later earned them the Nobel Prize. The emergency was an opportunity. The knowledge was the strength necessary to exploit it. In a clear example of offensive strategy, ModeRNA maintained and developed further their strength.

We could tell a similar story about BioNTech, which in fact is currently litigating with ModeRNA over certain aspects of intellectual property and keeping the two Nobel Prize winners at odds, but that is another story.

2. The defensive strategy: maintaining strengths to face threats

After decades working to maximize customer satisfaction and expand product range, in the 1990s Sigma-Aldrich was a leader in the sale of reagents for research. The business model relied heavily on postal delivery of thousands of catalogues. The “Big Red”, as we called the Sigma catalogue internally, as well as the Aldrich catalogue, sat in all laboratories in the world and scientists often used them as reference manuals due to the amount of information they offered on more than one hundred thousand products.

And then came the internet – and, with it, the first offer aggregators and price comparison platforms. It could have been the end of the business for a company with such a defined route to market. But the data and internal processes that had allowed to develop the best catalog in the industry were the strength necessary to confront the threat. The company focused the efforts on quickly transferring all this information to the Internet, creating what was the main e-commerce website in the sector for the following decades. The value of the domain for researchers was so important that even today, years after the acquisition of Sigma-Aldrich and its integration into the Merck group’s brand portfolio, Merck’s e-commerce website for research is still called sigmaaldrich.com

3. The reorientation strategy: correct weaknesses to exploit opportunities

A mail DVD rental company does not seem to be the best prepared candidate to take advantage of the opportunity offered in the 2000s by the birth of streaming content distribution. And that was Netflix in 1997. When the entertainment paradigm changed and physical disks began to give way to content platforms, Netflix transformed itself, preparing to create and transmit their own shows. They corrected a weaknesses in time to be able to exploit an opportunity. Starting with a small number of movies and series that people watched on computers, it grew to be the entertainment giant with more than 200 million subscribers. It is one of the best-known examples of successful reorientation, correcting weaknesses to exploit new opportunities.

4. The survival strategy: correct weaknesses to adapt to threats

Survival differs from reorientation in the sense of urgency. It is not about correcting weaknesses to take advantage of a good opportunity, but to avoid potential disaster due to a threat. In this case we will not use a corporate example: we have hundreds of admirable examples in our neighbourhoods. Think of that restaurant that learned to become a food delivery service during the 2020 confinement. Or that bookstore that, faced with the threat of Amazon and electronic books, evolved into a café-bookstore, learning to manage a snacks and drinks business and to organize social gatherings and cultural events. And so many others that found their way to correct existing competitive weaknesses to survive.

Continued learning

Since the mid twentieth century when the SWOT was born, strategy schools following the design one have placed more emphasis on continuous transformation, change and, currently, ecosystems. SWOT analysis is still useful in the new landscape, but only if we understand that it is not something static, but a starting point for a continuous learning process. Today’s strengths and weaknesses may be irrelevant in a few months, and next year’s opportunities and threats may not be visible at all today.

The examples discussed show how a good view of the internal and external situation can help us choose and prepare for the challenges we face. You can apply this to your company or your personal project.

But good analysis is useless if it is not accompanied by a continued learning mindset.

For the company and for the person.