What did you do today at work?

Which of those things you did are directly connected with the company’s strategy? How do your efforts contribute to executing it?

If you do things that do not contribute to the strategic goals, why do you do them?

Perhaps we need to take a step back and ask: do you know what the strategy is?

Or maybe even further back: is there a strategy?

* * *

Not having a strategy is like sailing at the mercy of the wind. Every day that we don’t sink is a success, but we don’t know which port we want to reach. It is possible to survive like this, but be careful: if you don’t know where you’re going, you may not like the place once you get there.

Having a strategy and not communicating it is what happens when strategic planning is just an academic exercise. Part of a nice ‘pitch deck’, something that no one really cares about. In practice, we remain at the mercy of the wind.

Many companies do have a good strategic plan, and they communicate it correctly, but they don’t execute it. There is no clear connection between the strategic goals and what gets done and measured. Such a connection would ensure that the strategy is everyone’s business.

A strategy is a decision about which goals to pursue and how to achieve them. By choosing a destination and a route, we discard others. That is why a strategy is also, and above all, a decision about what not to do. Strategy determines priorities. Allowing part of the organisation’s efforts to be disconnected from the strategy is a waste of efforts.

‘In a strategy, what you decide not to do is as important as what you decide to do’ (Michael Porter).

The model

Probably the best model to ensure the execution of the strategic plan at all levels in commercial organisations is the one of Robert Kaplan and David Norton.

Interestingly enough, before talking about strategy maps, Kaplan and Norton defined the balanced scorecard. In other words, it was a measurement model rather than an action model. This makes sense because measuring the right indicators is the first step in working on the right priorities.

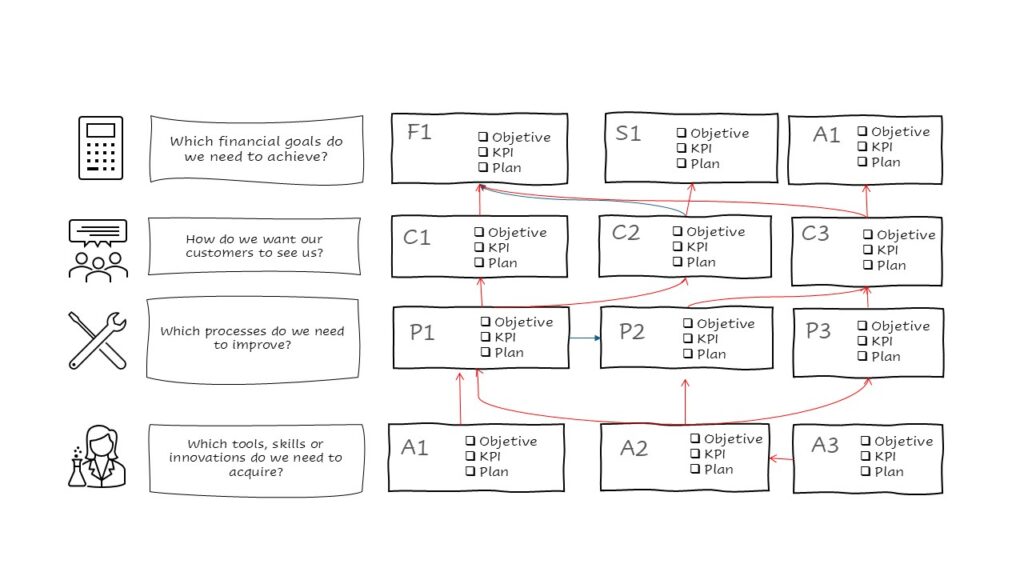

These authors challenged traditional management systems, which focused on setting objectives and measures for financial aspects only. Looking only at the income statement tells us where we are, but not how the machinery is moving. They proposed a balanced scorecard that established objectives, measures and actions at four levels:

• financial,

• customer focus,

• operational excellence, and

• learning and innovation.

To build the strategy map, management needs to ask themselves questions that set expectations at all the four levels, starting on the top.

Financial objectives

What do we want to see in the income statements? Growth or productivity?

If we are pursuing growth strategies, we could set financial objectives related to building the business (e.g. by opening up a new market) or increasing customer value (e.g., improving the repurchase rate or reducing the average discount).

In productivity strategies, we will choose goals reducing costs or improving the use of assets. Examples of finantial objectives in these strategies include sharing certain resources or reducing stock or collection days.

Customer-related objectives

Once we have a short list of strategically consistent financial objectives, we go one level down to make it possible. What our customers see will determine what shareholders see in the P&L.

Which selected customers are we targeting? You can not do everything right for everyone all the time. Once again, we need to make choices. Do we focus entirely on key customers or do we seek to expand our audience? In which segments?

Once the target customers have been selected, we can set objectives related to customer perception (e.g., satisfaction indicators, net promoters, etc.) or related to loyalty, lifetime value, etc. How do we want our customers to see us?

Internal process objectives

To make this customer perception possible, what do we need to do absolutely right?

It is time to identify the specific processes that key to improve. And, once again, trying to improve everything leads nowhere. Remember, a strategy is a choice. Will we differentiate ourselves from the competition through our product leadership, customer intimacy or operational excellence factors?

If our strategy is to differentiate ourselves through our product, we will probably focus on improving innovation, invention, development and beta testing processes.

If the key differentiator is customer intimacy, the processes we want to improve will probably be customer service, commercial management, or the creation of custom solutions.

And if we try to differentiate ourselves through excellence in internal processes, we will work on costs, quality, deadlines, procurement, production capacity management, etc.

There is a very long list of processes that we might want to improve, and it is different for every company. We have to choose the ones that will take us where we want to be: to our predefined customer and financial objectives.

And so we come to the fourth level, which is the most interesting.

Learning and innovation

At the base of the pyramid are the people. If we do not invest to equip people with the necessary training, the technological tools they need and a motivating environment conducive to their growth, it is impossible to build excellent processes, satisfied customers and financial results.

Key questions at this level might be: what are we missing? What knowledge, tools, or skills do our people need? Do we need to incorporate new technologies and learn how to use them? Do we need changes in our work culture, relationships, or motivational factors?

* * *

If we are able to make these objectives quantitative by assigning KPIs to all of them, we will have a balanced scorecard. We will have a set of measures that tell us whether we are making progress on our strategic priorities.

But we still don’t have a map. A map doesn’t just tell us where we are; it shows us where to go.

The strategy map

To evolve from the balanced scorecard to a strategic map, the next step is to establish cause-and-effect arrows between the different objectives, so that each one leads to others at a higher level.

For example, a learning objective such as ‘install and learn to use new CRM’ could lead to ‘reducing errors in customer service’, and this to ‘increasing customer satisfaction by 10%’. Finally, there will be an arrow that ends in ‘increasing sales in market X’.

Finally, each of these objectives must be associated with an action plan. The teams involved in executing them need to participate at this stage. The purpose is to align what everyone does with the execution of a shared strategy.

You might identify transversal action plans which affect more than one of the strategic objectives. These powerful plans are called strategic initiatives and should receive special attention from management.

This map will be useful to align the efforts of all only if it becomes THE fundamental tool of the management team. These indicators are the only ones that interest the CEO and his or her management team. These action plans set the priorities for the work of each team or department.

The organisation must also be aligned with the strategy. This means that these strategic priorities determine job descriptions, department set up and incentive plans. We cannot say that the strategy is to develop customers in Portugal and still give commissions only for sales in Spain. Or call customer satisfaction a goal but get rid of talent in the customer service department.

Critical observations

These are bad times for strategic planning. Everything is supposed to be volatile, uncertain, changing and ambiguous. Some experts claim that it is better not to make plans: simply respond to changes in the environment. That mindset creates survivor companies, not purpose-driven companies. Let’s not use the VUCA concept as an excuse: not everything is unpredictable. But in fact changes are happening faster than ever before. Strategic plans can no longer last five years, not even three, and they have to be changed while they are in force. The balanced scorecard and the strategy map must be adapted to changes as often as necessary. Due to the simplicity of the model, nothing prevents us from changing objectives or adjusting them when appropriate.

Another possible criticism comes from the fact that the objectives are arranged hierarchically and the arrows always point upwards. This seems to indicate that financial results are always the ultimate goal, and everything else is geared towards achieving them. Is this compatible with conscious capitalism and companies committed to social or environmental objectives?

This issue was explored by Kaplan himself, together with David McMillan and other authors. In a 2021 article in HBR, they present several approaches. The Amanco case proposes splitting the goals to show social and environmental goals at the same level as the financial ones and also attracting arrows.

There is potentially a simpler way to adapt the concept to conscious organisations. We could allow ourselves to draw downward arrows. In other words, some of our objectives relating to people and innovation would be prioritised and would attract the flow of arrows towards them, even from financial objectives. Why not?

There are other models to put strategic objectives into action. Implementation plans, OKR, etc. But in my opinion, none are as simple and comprehensive in their approach.

The authorship of the idea has also been debated. As with so many consulting models, Kaplan and Norton developed their idea through trial and error in collaboration with their clients, so part of the credit goes to those clients, as Analog Devices claims. But it is fair to attribute the map to those who organised the ideas and developed a general model with them.

My main learning after having implemented this model repeatedly in several organizations is the fact that all departments and all people need to be part of the execution of the strategy. This means not only that everyone does things to reach the destination port. It also means that everyone stops doing other things that do not help to reach it.