The scientific team in “A”, a biotech start-up, is made up of professionals with long experience in research and excellent knowledge of their technology. They usually work with autonomy, need little support, and are happy walk the extra mile when their knowledge can help. The CSO’s job was easy until now, mere coordination. But something has changed. Management wants to prioritise efforts to sell the MVP they have developed, and their help is needed. Expectations are changing regarding what good looks like, all company communication is becoming very commercial, and the scientists are being pushed out of their comfort zone. They do not know how to go quickly through the expected transformation. Insecurity causes irritation. Being seen as senior professionals, management does not feel it necessary to offer them many explanations or meetings, but informal conversations to share frustration and confusion multiply. The atmosphere is less and less productive.

…

C. has worked in corporate communications for many years. In her first week at the company she has to prepare and present a town hall. She is excited and nervous. She counts on her experience, her communication skills and a sincere desire to make an impact. But she doesn’t know if she will have a lectern or be able to move around the stage, she hasn’t received the final figures she has to announce and still has doubts with some internal jargon. Time is flying by and she is finding it difficult to finsh a good script and deck. That is why she is nervous. She tells her director: “I don’t know how I’m going to do it”. The director, in her very delegative and trust-based management style, replies that she should not worry, she will do well because she has a great deal of experience. But yes, C. is worried. Who would have anticipated she would yearn for more directive leadership?

…

P. is a sales engineer with decades of experience. His customers rely on him to solve complex product application questions because they value his knowledge. When he works with enthusiasm, he is able to close challenging sales opportunities with strong competition, technical complexity and price pressure. But organisational changes have been announced that he is not happy about. He fears losing some of his freedom, recognition, or even his job as he knows it. He tries not to let this impact his performance, but all those doubts drain his energy. One day he walks into his manager’s office and says “I’m confused, I don’t see my role clearly”. The sales manager, in managerial style, gave him some very precise priorities for the next two weeks. “Clear now?” “Yes”. A month later, P. has found another job.

The leaders in these examples have very different leadership styles, but one thing in common: they failed. So which is the most effective style?

Situational Leadership. The model

Back in 1969 Paul Hersey and Kenneth Blanchard proposed in Management of Organizational Behavior that there is not one style suitable for all situations, nor do you have the luxury of choosing the style you like. Effective leadership requires adapting your style to the situation in a dynamic way.

Their model is known as Situational Leadership and is the first tool a new leader should learn.

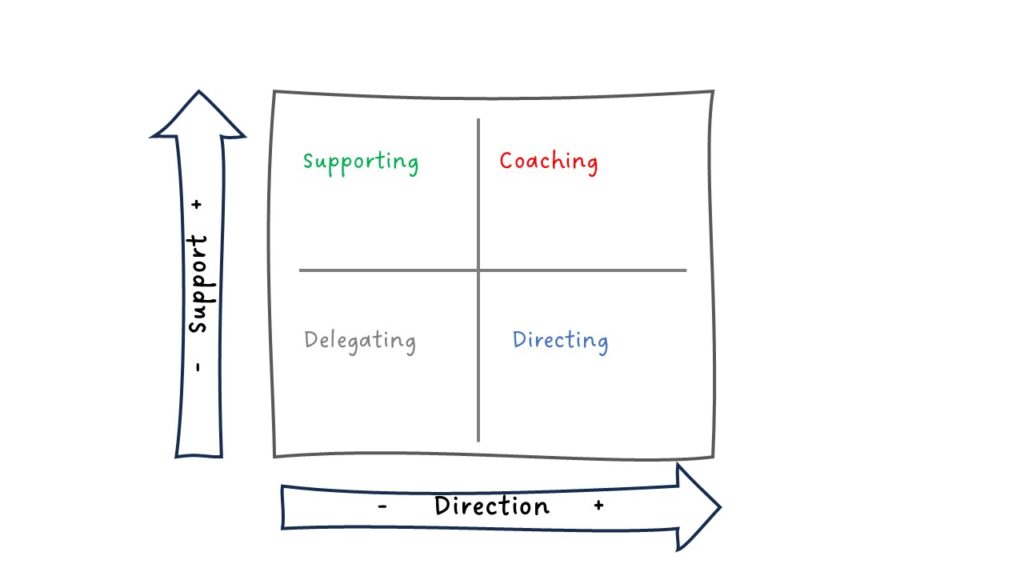

According to situational leadership theory, finding the right leadership style for each situation is a matter of combining two ingredients in the right doses: direction and support.

The need for more or less direction and support is determined by the readiness of the employees. By adapting the intensity of each of the two components to different situations, leaders can accompany employees in the right way to maximise results.

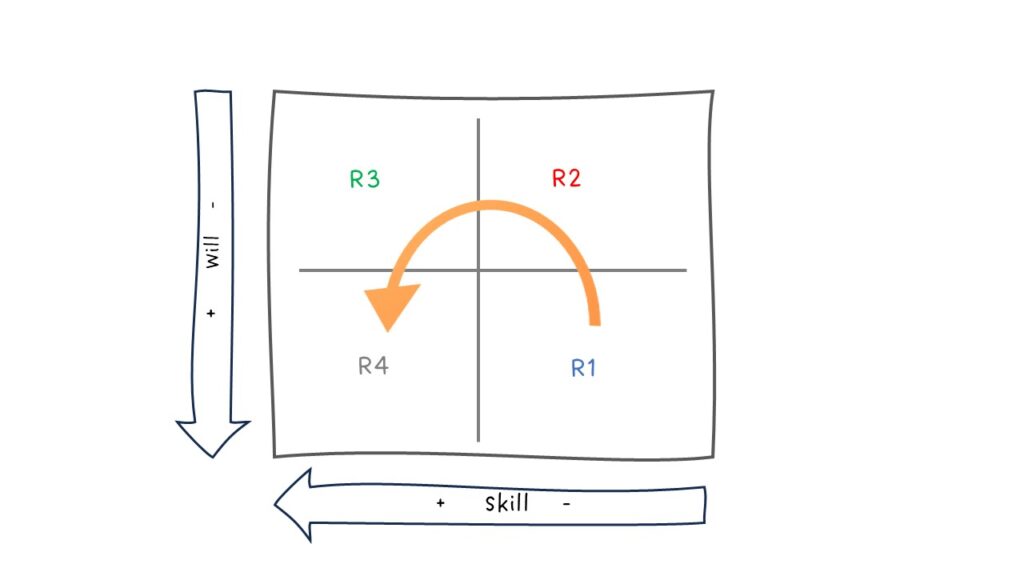

But people do not walk around the office with a professional readiness meter on their foreheads. So how to estimate it? Defining and diagnosing maturity levels is the difficult part of the model and any attempt is an oversimplification. Even between Blanchard and Hersey there were different proposals, these were readjusted over time giving rise to Situational Leadership Theory II, and they eventually separated and developed two different methodologies of application.

The common line in the different versions is defining readiness at work based on two observable dimensions: skill and will. The latter is actually a combination of motivation and self-confidence.

Typically, in an initial phase (R1), employees need much direction because at that stage they don’t know the job. In that situation, involvement is practically irrelevant and emotional support does not help: we need to learn everything. When we are there as enployees, we need a directive leadership style.

Then doubts arise and emotional support is needed, although instructions are still required because there is still a lot to learn. The person knows the elements of our work but is not yet comfortable analysing them and making decisions. At this second level of readiness (R2), employees need a coaching leader who offers both intense direction and support.

Gradually, learning is completed, but motivational difficulties persist, or perhaps grow as the honeymoon with the company has finished. Employees can then make proactive proposals but find it difficult to make decisions, due to lack of confidence or motivation. In this phase (R3) people need less direction (micromanagement is not welcome), but intense support is needed. The leadership style is participative.

In an ideal process, we can expect a final R4 phase where people need hardly any support or direction, only full delegation. They have the knowledge and self-confidence to make quality decisions without fear. In that phase, teams give little work to their boss. His or her leadership style will be delegative.

It sounds easy. If leaders are able to direct and support, they should be able to find the right mix of both activities that fits the situation…

However, we fail all the time. Beginner leaders often do not understand the model well enough to make good use of it, and those of us who are more experienced continue to make mistakes.

Why is it so hard to read situations correctly and understand needs?

For the same reason we struggle to sell, connect with our teenage children, or retain talent. Because we don’t listen. Listening involves observing with openness and curiosity. Istead, we observe from our biases, our expectations and our experience.

Why isn’t it working?

Despite my preference for this model, I think the first mistake we tend to make is taking it too literally. If we have learned this theoretical way and try to superimpose it on what we observe, it becomes a bias. A model serves to help us predict what is likely to happen to a person, not to determine it. Every employee is unique. In real life, not all people go through the same phases. We do not all spend the same amount of time in them, and these phases can always be reversed.

The science team in A had everything to be an autonomous team. However, they reverted to the level where they needed intense support and clear direction as a result of an unexpected crisis. There was a jump from maturity 4 to maturity 2, difficult to foresee and the CEO in the example failed to detect it.

The second mistake is looking from the perspective of our own experience. We say: “I’ve been there and I know what you need”. We are all different, our speed of learning is influenced by many factors and our emotional involvement in the work by many others. There is no common path. Probably C’s manager had a very different first contact with the challenges of communication. Perhaps her beginnings required an effort of self-confidence but not a special need of content knowledge.

The third mistake is observing from our expectations. We assume people will behave the way we need them to do. The inner dialogue of P.’s boss or his discussion with a leadership coach could probably go like this: “No, P. cannot be in a state 3 of readiness, demanding emotional support at this stage. Come on, I need him at stage 4, totally self-sufficient. He’s old enough and experienced enough for that. Otherwise, we have a very serious problem”. And he has got one thing right: he has a very serious problem. But he has forgotten that solving it is part of his job as a leader.

You should not try to fit the team’s behaviours into your own expectations, your experiences or your theoretical model. Instead, you should listen.

Listen, listen, listen

Listening includes observing behaviours, asking questions, connecting answers, obtaining evidence and references.

Adults often ask questions just to confirm our knowledge or assumptions. That is why we ask questions so badly. We ask closed questions, we propose alternative answers, we wrap the questions with endless comments. The most practical way to learn how to ask good questions is observing how children ask. They ask to know. Their questions are born out of genuine curiosity.

A Team, how do you see yourselves coping with the change?

Q., how do you feel?

C., what do you need?

Leaders and salespeople of a certain experience are usually trained to ask questions. But then you also need to listen to the answer.

Good listening stems from a genuine and respectful interest in what we are hearing. If there is such an interest, the listening will have some characteristics that the other party will recognise as active listening.

- We have eliminated distractions, we are totally focused on the conversation. No mobile phone on the table, no asking for a moment to read an important email, no glances over the speaker’s shoulder towards the door. A small gesture kills a conversation.

- We nod or make some other gestures to confirm that we are accompanying, that we are still there.

- If there is any doubt, we ask questions or rephrase, to confirm good understanding. But other than that, we don’t interrupt. We never anticipate what we are going to hear.

Don’t learn by heart these attitudes to give the image of an active listener. This is not about pretending to listen; it is about listening. Just develop a sincere curiosity about what the other party has to tell you, and the indicators of active listening will occur spontaneously.

Putting this into practice will be very difficult if we continue to think that the team is at the service of the leader’s success. If we confuse leading with exercising power. Only if we understand that the leader’s job is to make the team’s success possible, it will come naturally.