“I don’t have time”, we all say. It’s almost a sign of status: not complaining about lack of time makes you appear unimportant. However, time is the only thing we have. Your belongings come and go, but time walks with you as long as you live. Or perhaps, as the philosopher Julian Serna says, we do not have time: we are time. We all have (or are) the same amount of time: 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, for an unpredictable number of weeks.

So the first suggestion for our reflection on the use of time is this: let’s change the language for a moment. Instead of saying “I don’t have time”, we can say: “I try to do, or am expected to do, more things that can be done in my time.” The new wording gives us some clue as to what the solution to the problem may be, doesn’t it?

Since time cannot be bought, sold, or modified, let’s admit it: it cannot be managed. Perhaps time management workshops should be called productivity management instead. And, once again, stating the problem in the right words points us towards the solution. Our aim should be to find a method that will allow us to choose what to do in our time in the way that works best for us. And also what not to do.

It is not easy. In the following lines, we will look at some models that can help us, so you can pick and study the one that suits you. At the end we will focus on the most critical need for our productivity: managing attention.

Urgent or important?

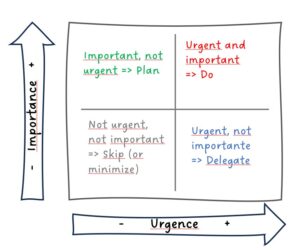

Probably the best known tool in productivity management is the Eissenhower matrix, and it is still interesting. Based on a 1954 speech by the US president, this model for classifying incoming tasks is based on an important distinction: urgent is not the same as important.

We can classify actions according to their urgency and importance in four quadrants:

- Important but not urgent actions must be scheduled – that is, assigned a date and time in our agenda.

- Urgent and important actions must be executed immediately.

- Those neither urgent nor important should be ignored. If we do not have the power to ignore them, due to bureaucratic rules that bind us, let’s do them with the minimum investment of time possible. It is important to remember that a task tends to expand until it takes up all the time we allocate to it. In these less urgent and unimportant tasks, we must set a strict limit on the assigned time.

- Those that are urgent but not important to our job, are probably important to someone in another role. Therefore, the best option is to put these tasks in the hands of the right person.

In practice, this fourth quadrant is often poorly managed. Delegating is difficult. You must train yourself in good delegation practices. Delegating requires a method, which is based on agreement, good communication and recognition.

This matrix is useful for screening incoming tasks, and is necessary in your productivity system, but it is not sufficient. In a well-organized time, reacting to the tasks that come in is not all you will do.

Stress-free productivity?

David Allen’s Getting Things Done method is a big hit in the field of personal productivity. It has unconditional fans, probably because it is based on common sense and on a good knowledge of how our brain works. It seeks relieving us from the stress caused by retaining incomplete tasks in memory.

Once the GTD system is implemented, all the ideas or possible actions that enter your mind will go through an inbox (physical or virtual) where you will clarify and organize them:

- If it does not require action nor is interesting for the future, discard it.

- If it does not require action but you want to keep it for future reference, archive it.

- If action is required, Allen replaces the Eissenhower matrix with the two-minute rule:

- If the action can be completed in two minutes, do it.

- If the action cannot be completed within two minutes, there are two possible routes:

- Does it have a fixed date? Note it down in your calendar

- No fix time? Note it down in a next actions list, that you will review daily.

Allen gives us extremely detailed recommendations for each of these steps as well as for managing projects. A thorough implementing of the method requires two or three days dedicated to reinventing your workflow. If now is not the time to do this full immersion, you might want to apply it in a simplified way to email management.

Poorly managed Email is an enemy of productivity. Many people spend their workday answering emails and, only at the end of the day, when these stop coming in, do they begin to feel they are working. Ian Charnas’ Inbox Zero method is a simple adaptation of the GTD philosophy to email than can help in those cases.

Allen gives little importance to priorities, because the GTD method seeks to complete all the actions we want or must do. But most of us mortals know that we are not going to do everything that we want or are expected to do. The question then is what do we sacrifice? And that’s where the concept of priorities comes in.

When do you do what really matters?

Priority in this context is not what is done first, but what is planned to secure it is done. In other words: not the most urgent, but the most important thing. But what are the criteria to define important? Important to whom?

The most important task is not the one that comes from the most impatient client or colleague. The most important tasks for you should be those that in your judgement will contribute most to achieve your goals, in line with the values you are committed to. I can’t tell you what your priorities are. Neither can your clients or your colleagues… not even your boss.

This does not mean that we can live with complete freedom ignoring the expectations of those around us. Life involves adapting, negotiating, accepting balances of power. Unless you are a billionaire and independent, it is very likely that meeting the expectations of your clients and your boss is very important to you and greatly influences your priorities. But these are still yours.

Once we agree that you set your priorities, the next suggestion is to have a structured method for doing so. The method that I practice and train involves identifying the activities we do to achieve our goals, and prioritizing them at three levels, depending on:

- how important the objective is to which this activity contributes,

- how much it contributes,

- and who it impacts.

Once the highest priority tasks have been identified, we must allocate time for them in our agenda. In other words, we plan.

If this is not done, unimportant activities can expand and take almost all of our time, and we only do what is important when the noise of the secondary stuff allows us. That may occur outside of work hours, or it may not occur at all. That is why it is mandatory to plan the most important tasks. To plan, you need a hierarchy of priorities, some experience to estimate in a realistic way the time needed, and a calendar.

Doing the exercise of prioritizing and planning together as a team, in a workshop facilitated by someone external to the organization, is a transformative exercise. I makes teams review asumptions, align priorities, discover inefficiencies and negotiate agreements. That’s why the (misnamed) time management workshop is one of my favorite activities to do with teams, and one of the most intense.

In a nutshell, and now ordering the steps, the sequence should be:

- Assign priorities

- Plan priority actions, allocating enough time them and reserving some time for the entry of new tasks

- Manage the incoming new tasks (optionally with the Eissenhower matrix)

- Manage task flow (optionally with GTD)

But even if you have a perfect prioritization and planning system and a very well designed task flow, it can all fall apart when distractions come.

Managing attention

To deliver the promises we have made to ourselves we need significant self-discipline, and this requires that we regain control of our attention.

Staying focused was never easy, but these days it’s almost heroic. Everyone expects immediate responses from us to everything, the excess of stimuli is infinite and, to complicate it further, there are businesses whose profit is based on distracting us, because our attention is their product. What can we do to keep attention thieves at bay?

We need to manage external distractions, agreeing to certain rules with those around us, and also self-distractions, with some mental hygiene practices.

Three basic (but not easy) recommendations are:

- Disable all email, WhatsApp, and social media notifications right now. You decide when it is the time to read the incoming messages. This takes some courage because society expects you to always be available and ready to respond. It’s worth rebelling.

- Agree with your team mates on basic rules about interruptions. The open space of offices and instant messaging or chat are terrible enemies of productivity and sources of stress. Sometimes, also the collaborative spaces of company intranets. You have to talk about it and agree on limits for its use.

- Take breaks every two hours at most. During those breaks, get up physically from your workplace, drink water and move. Watching videos or reading tweets is not the way to rest, and you know it.

Managing attention is probably the hardest of all, but also the most important. Our attention is our treasure. Why give it away?

It will gradually become easier if we train our attention with some regular practice of yoga, meditation, mindfulness or a sport or concentration activity that attracts us.

I still have one final question. Have you read this article during your reading time? Or, on the contrary, there is nothing in your calendar like “Reading time”, and you have gone through it when it came to you on LinkedIn, with impatience and with a certain feeling of guilt because you are reading and not working or enjoying your family? Give it a thought.